The use of illegal narcotics in the United States has varied over the years, but by many accounts – including the president’s – the nation has never been so high on drugs.

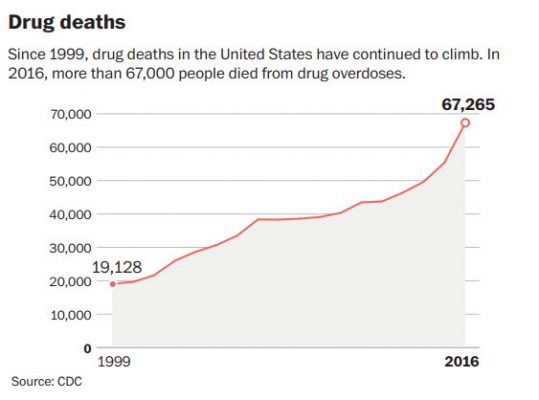

Seizures of methamphetamine and heroin at the Mexican border have surged. Cocaine use is spiking again. The opioid epidemic has pushed overdose deaths past 60,000 per year, a record.

“We used to have the ‘Age of Aquarius.’ Everyone thought that was a big drug age,” President Donald Trump said this month, evoking the 1960s counterculture. “That was nothing compared to this.”

Attorney General Jeff Sessions is set to deliver a speech Monday in Pittsburgh on two of his signature issues: violent crime and the opioid epidemic. He has implemented a tough new charging and sentencing policy, urging federal prosecutors to use every available tool to crack down on violence. And late last year he announced that anyone who possesses, imports, distributes or manufactures fentanyl – a powerful synthetic opioid – can face criminal prosecution.

The president and his attorney general have blamed the drug boom for “American carnage,” but the latest crime statistics suggest that the relationship between illegal narcotics and violence in U.S. cities is not so clear.

In Atlanta, Houston, Los Angeles and other hubs of the drug trade, the homicide rate decreased last year. Major American cities appear to be getting safer even as they are flooding with dope.

Nowhere is this trend more pronounced than in New York City. Inundated with heroin and fentanyl, the city tallied nearly 1,400 fatal overdose deaths in 2016, a record. But police reported just 290 homicides last year, the lowest total since 1951 and an 87 percent drop from 1990, when there were 2,245 killings.

The odds of being killed in New York City are about the same today as they are in Montana or Wyoming, even at a time of record-breaking narcotics seizures.

In Los Angeles, the biggest West Coast hub for heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine, homicides fell 6 percent in 2017 and 20 percent in Los Angeles County. The homicide rate also dropped by double digits last year in Houston, Washington and even Chicago, where violence was so bad a year ago that Trump threatened to “send in the Feds.”

These statistics present what appears to be a broad, long-term decoupling of homicide rates and the illegal drug trade in many U.S. cities, a trend that upends conventional wisdom about the origins of urban violence.

Criminologists see many potential factors, but one may play the biggest role in reducing drug-related killings: smartphones.

Just as mobile technology has transformed ordinary commerce, it has revolutionized illicit markets, too, making the drug trade more predictable and less lethal. GPS mapping, encrypted communications and messaging apps have vastly reduced the need for drug dealers to physically control urban spaces and defend them with deadly force, experts say.

“The technology of retail drug dealing has shifted radically, especially over the past 10 years,” said Mark Kleiman, a criminologist at New York University. “It’s no longer people standing on street corners. It’s hand-to-hand transactions between people with cellphones, and they’re not vulnerable in the same way.”

Added Kleiman: “It’s also harder for police to disrupt.”

There are many U.S. cities where the drug trade still largely operates in traditional ways, including Baltimore, whose 343 killings last year were an all-time high. Open-air drug markets remain engines of violence in St. Louis, New Orleans and other cities with elevated homicide rates.

But that business model is no longer dominant everywhere, and certainly not in cities with large numbers of middle-class drug users who can arrange deliveries on iPhones instead of driving into high-crime neighborhoods.

Federal narcotics agents last month busted a heroin distribution ring in Southern California dubbed “Manny’s Delivery Business,” whose dispatchers took hundreds of orders per day for heroin and cocaine, sending couriers to meet customers at designated spots. The Drug Enforcement Administration called it “a heroin distribution machine.”

In Houston, where the homicide rate decreased 11 percent in 2017, narcotics officers have learned to watch online commerce such as EC21. A search for “fentanyl” on the site will show zero results. But spelling it “fentanylll” reveals a thumbnail photo of white powder with a phone number and an email address, possibly from a shipper in China.

“When I first started in narcotics in 1998, you’d drive into an apartment complex and have people reaching in your window,” said Lt. Stephen Casko, a Houston narcotics officer. “Now you can just order drugs through the mail and never have to deal with another person.”

Postal inspectors at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport seized nearly 80 fentanyl shipments last year, a threefold increase from 2016. Federal agents in Atlanta last summer arrested 16 postal workers, accusing them of taking bribes to deliver kilo-sized loads of cocaine with their mail trucks.

Sanho Tree, an advocate of drug decriminalization at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, said there is “no organic link” between drugs and violence. “But there is one between illegal drug markets and violence,” he said.

Drug dealing in the 1960s and 1970s was relatively nonviolent, Tree said: “Usually it was a dealer with a backpack going door to door to make private deliveries.”

That changed with the introduction of mandatory minimum sentencing, he said, which left street-level dealers facing long prison terms. “It made it too risky to hold a backpack full of drugs, so that created a market incentive for an open-air drug market model operated by minors – lookouts, runners and so forth” – who would not face the same harsh penalties.

Dominating and defending physical space were the key to big profits. “That’s why street corners became so valuable” Tree said.

Rates of violent crime in the United States – homicides in particular – peaked in the 1980s and early 1990s, when cities were besieged by crack cocaine. But when use of the drug waned, along with falling levels of cocaine and heroin consumption, homicide rates also receded.

Today, the nation’s per capita homicide rate is about half what it was in 1985. Criminologists attribute the drop to a range of factors, including better policing, more job opportunities and even the possibility of declining lead exposure.

After reaching historic lows in 2014, homicide rates in many U.S. cities rose abruptly in 2015 and 2016. Experts have noted that even with these increases, violent crime levels remained near historically low levels and were much higher a quarter-century ago, but the sudden rebound became a focal point for Trump and his administration’s law-and-order initiatives. “Violent crime is back with a vengeance,” Sessions declared, promising to remedy it with tougher prison sentences, a crackdown on illegal immigration and the transfer of more military hardware to police departments.

Nationwide, the number of homicides rose 1.5 percent during the first six months of 2017, compared to the same period a year prior, while violent crime overall – including rape, robbery and aggravated assault – was down slightly, according to FBI data released in late-January. Homicides were up in the South and Midwest. They were down significantly in the Northeast and slightly in the West.

Sessions, writing in USA Today, characterized the new statistics as evidence of the administration’s early success. “When President Trump was inaugurated, he made the American people a promise: ‘This American carnage stops right here and stops right now,’ ” Sessions wrote, quoting from Trump’s inaugural address. “It is a promise that he has kept.”

But in many U.S. cities, the violence didn’t come back very far. Some places that had the biggest spikes, including Chicago and Washington, once more have declining homicide rates.

The psychotic effects of narcotics also may be a factor, criminologists say. Whereas crack cocaine often produces a rush of manic energy and supreme confidence, opioids leave users sedated and perhaps less prone to violent behavior.

Unlike the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, which hit poor African-Americans hardest, the demographics of the opioid crisis cut across geographic and class divides. Many of today’s addicts are middle-class users “who don’t live in neighborhoods plagued by violence,” said Volkan Topalli, a professor of criminal justice at Georgia State University.

“There isn’t a high baseline level of violence in those places,” he said, “and the distribution networks are not primarily controlled by large gangs.”

Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, said the opioid crisis appears to be the biggest factor behind rising homicide levels among white Americans since 2014. But he said the increase probably would be far higher “if we still had as many of the street-level drug markets that were widespread 25 years ago.”

There appears to be another element to the new era of American narcotics trafficking that also may explain the homicide trends: a deliberate effort by Mexican drug cartels to minimize the use of violence on the U.S. side of the border.

The same smuggling organizations that have pushed Mexico’s homicide rate to its highest-ever levels operate by a different logic in the United States, just like the large corporations that leverage economic advantages afforded by the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Diverging levels of violence along the U.S.-Mexico border illustrate the pattern. Cities such as El Paso and San Diego have some of the lowest homicide rates in the United States, despite sitting opposite Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana, two of Mexico’s most murderous places.

The lack of a “spillover” effect is thought to be at least partly the result of a disciplined business strategy that seeks to avoid the attention of U.S. law enforcement, said Sam Quinones, author of “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic.”

Unlike the Colombian trafficking groups whose attempt to take over drug markets in Miami, New York and other American cities produced a wave of homicides a generation ago, modern Mexican traffickers largely eschew violence on the U.S. side.

“They have a very acute sense for the enormous difference between the criminal justice in Mexico and criminal justice in the United States,” he said. Fearful of a long sentence in an austere U.S. federal prison, the gangsters prefer to settle scores and adjudicate disputes with rivals in Mexico, where fewer than 5 percent of crimes lead to criminal convictions.

Quinones’s book describes a group of Mexican heroin dealers in the Denver area, the “Xalisco Boys,” whose couriers would drive around delivering drugs in little balloons. The drivers kept the balloons in their mouths and carried water bottles to gulp down the dope if pulled over by police.

The heroin dealers rarely remained in one U.S. city for long, and would cycle back and forth to Mexico often. They cared so little about their street reputations that they would sell to customers who had robbed or cheated them, treating the losses as business write-offs rather than personal insults to be avenged. They avoided high-crime areas and didn’t carry guns.

“A lot of these guys were just shy farm boys,” Quinones said. “They were intimidated by the United States, and definitely not interested in getting into internecine wars.”

And if the dealers felt threatened by law enforcement officials, or rival traffickers, they would simply pick up and move their mobile heroin business to another U.S. town or city. They believed the violence wasn’t worth the risk, Quinones said, “and the market in the United States was big enough for everyone.”

High-volume Mexican traffickers appear to operate similarly. When DEA agents in New York raided an apartment in Queens last year and found 141 pounds of pure fentanyl, they arrested a middle-aged couple who had arrived from Mexico a few weeks earlier.

It was the largest seizure of the drug in U.S. history, worth tens of millions of dollars, the DEA said. But the couple didn’t even have a weapon.

The Washington Post’s Mark Berman and Sari Horwitz contributed to this report.